Dr Catherine Hoad and Associate Professor Oli Wilson of the College of Creative Arts.

Opinion: NZ music’s #MeToo moment is a wake-up call for educators: prepare graduates to challenge and change the industry, say researchers Dr Catherine Hoad and Dr Oli Wilson of Wellington's College of Creative Arts.

Recent accusations of harassment and coercion by leading figures in Aotearoa New Zealand's music industry were shocking, but not surprising.

Last year, we released the Amplify Aotearoa report that revealed serious issues with gender diversity in the local music industry. Two main findings emerged:

- over 70% of women reported experiencing gender discrimination, disadvantage and bias

- nearly half of women reported they had felt unsafe in places where music is made and/or performed.

While there are initiatives encouraging inclusive and diverse cultures in music, women face a range of systemic barriers in the industry, including under-representation, earning less and receiving less airplay, winning fewer awards, and widespread harassment. These issues are experienced disproportionately by women of colour and gender diverse people.

The recent revelations of abusive behaviour in the industry remind us that, beyond its career-limiting potential, discrimination involves a significant emotional cost to victims. This was a major motivation for our Amplify Aotearoa research.

Empowering the next generation

As curriculum developers and university educators in a music degree, we felt obliged to better understand the industry our students were entering. In the process, the project identified even more obligations.

It is not enough for the tertiary sector to “call out” the problems the music industry is facing. Rather, we must also reckon with the role music education should play in breaking down obstacles and empowering the next generation of Aotearoa’s music makers to lead cultural change.

In recent years, many tertiary music providers have shifted their focus toward producing “real world” outcomes for their graduates. Music degrees have evolved with the goal of equipping students with proficiency across a variety of industry contexts. Work-integrated and project-based learning is prioritised, seeking to develop skills for career success and employability.

Such training aims to produce music graduates who are positioned to meet the demands of the industry, equipped with realistic attitudes and intentions about their pending careers.

Changing what and how we teach

What, then, should a “realistic” attitude entail, given the industry’s well-documented history of marginalisation, exploitation, and harassment of women and gender diverse people?

Training students for the reality of working in an industry in which they can expect to be likely targets of mistreatment shows complacency towards existing cycles of discrimination.

Encouraging students to develop “realistic” career intentions should mean empowering them not just to understand existing industry practices, but to have the tools to change them.

Part of the answer lies in what and how we teach. Critical theories that underpin our understanding of issues such as race, gender and sexuality allow us to engage with the ways music carries and constructs meaning in our society. In doing so, they provide us with the tools to understand the lived experiences of music industry workers.

But such approaches are at risk within the tertiary sector internationally, where staff and funding cuts have jeopardised courses that teach the critical skills essential to bring about change in our industry.

Addressing the gender imbalance

Further urgent issues facing the tertiary music sector are barriers to access, and the lack of diversity in our student cohorts. Who are we training and graduating into the industry?

Data provided by the Tertiary Education Commission show music cohorts in Aotearoa are largely populated by young Pākehā men from high-decile school backgrounds. Women currently make up around 40 per cent of enrolments in university music programmes and courses, and women are under-represented as staff across the sector.

This disparity is further amplified in the industry, with women representing 24.1 per cent of APRA-AMCOS NZ members. That the imbalance we see in the industry is evident in university recruitment figures suggests problems with pre-tertiary education too. It seems fewer women see music as a viable pathway for study than men.

Educational institutions are also not immune to the same issues of sexual abuse and coercion which have plagued industry, as recent allegations have shown. The tertiary sector must do more to foster diverse and inclusive cohorts and curricula, and hold institutional abuses of power to account.

Change from within

For music educators, this means advocating for critical approaches to understanding music, even when this may not always align with institutional definitions of employability.

It also means responsibly and meaningfully talking to our students about the epidemic of harassment in creative fields, addressing disparities in recruitment, and better understanding the social and economic factors that produce inequalities in student cohorts.

As researchers and educators, our aim is to forge a fairer and more inclusive environment for people to make and share music, but this also comes with the immediate obligation of addressing how the wider tertiary sector must effectively engage staff and students in what it means to be a responsible member of a music community.

It is the responsibility of music education to empower students to challenge existing industry practices and organisations, rather than simply place students within them.

More Research stories

Research

Doctoral candidate Kevin Miles has been awarded Dean’s List for Exceptional Theses

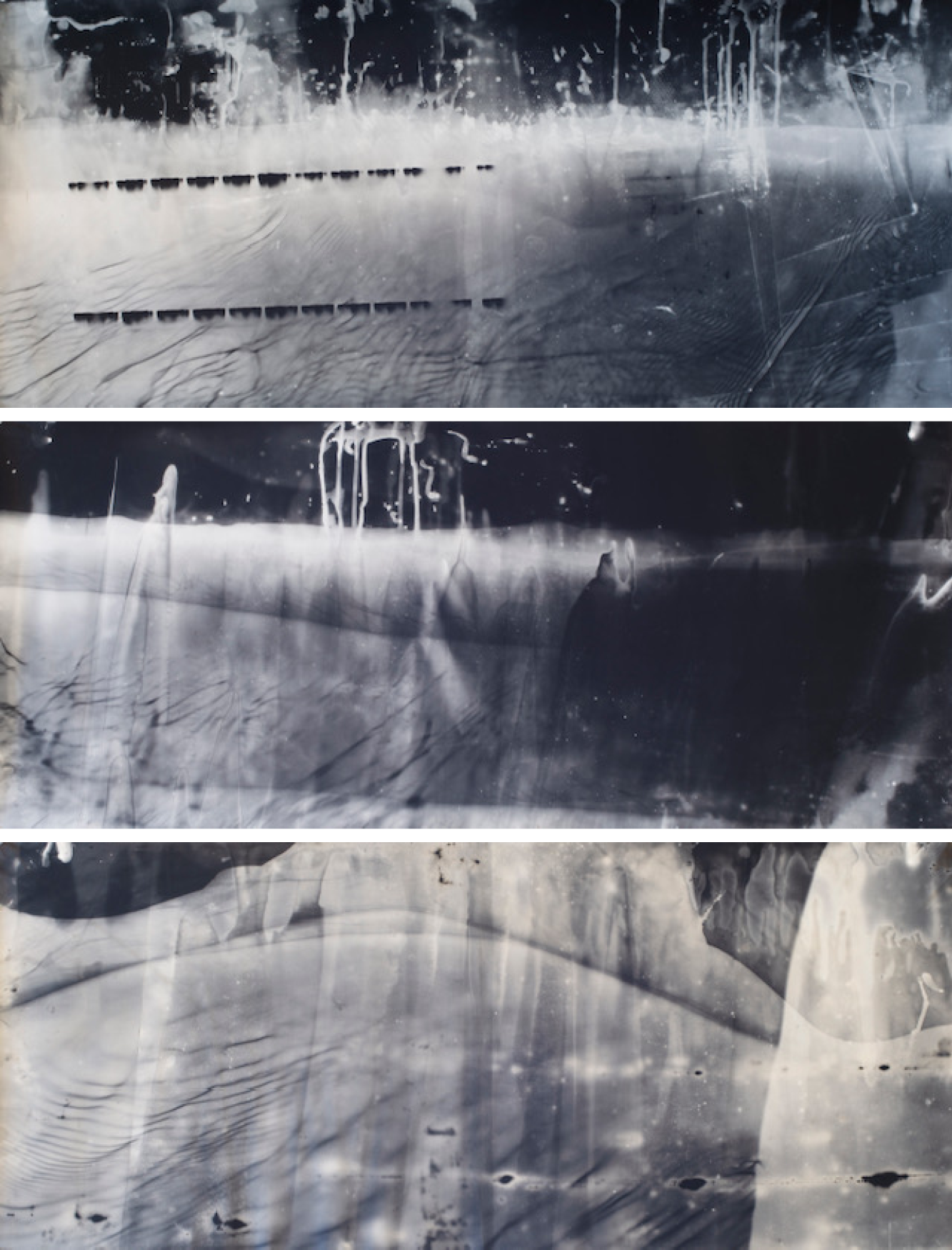

His creative based research has utilised the practice of ‘cameraless photography’ where photographic materials (film, photo paper etc) are used directly to record experience and phenomena aboard ship!

Research

Tackling poverty and institutional racism through design

Auckland architect John Belford-Lelaulu has won the Creative New Zealand and Massey University Arts and Creativity Award at the 2018 Prime Minister’s Pacific Youth Awards.

Research

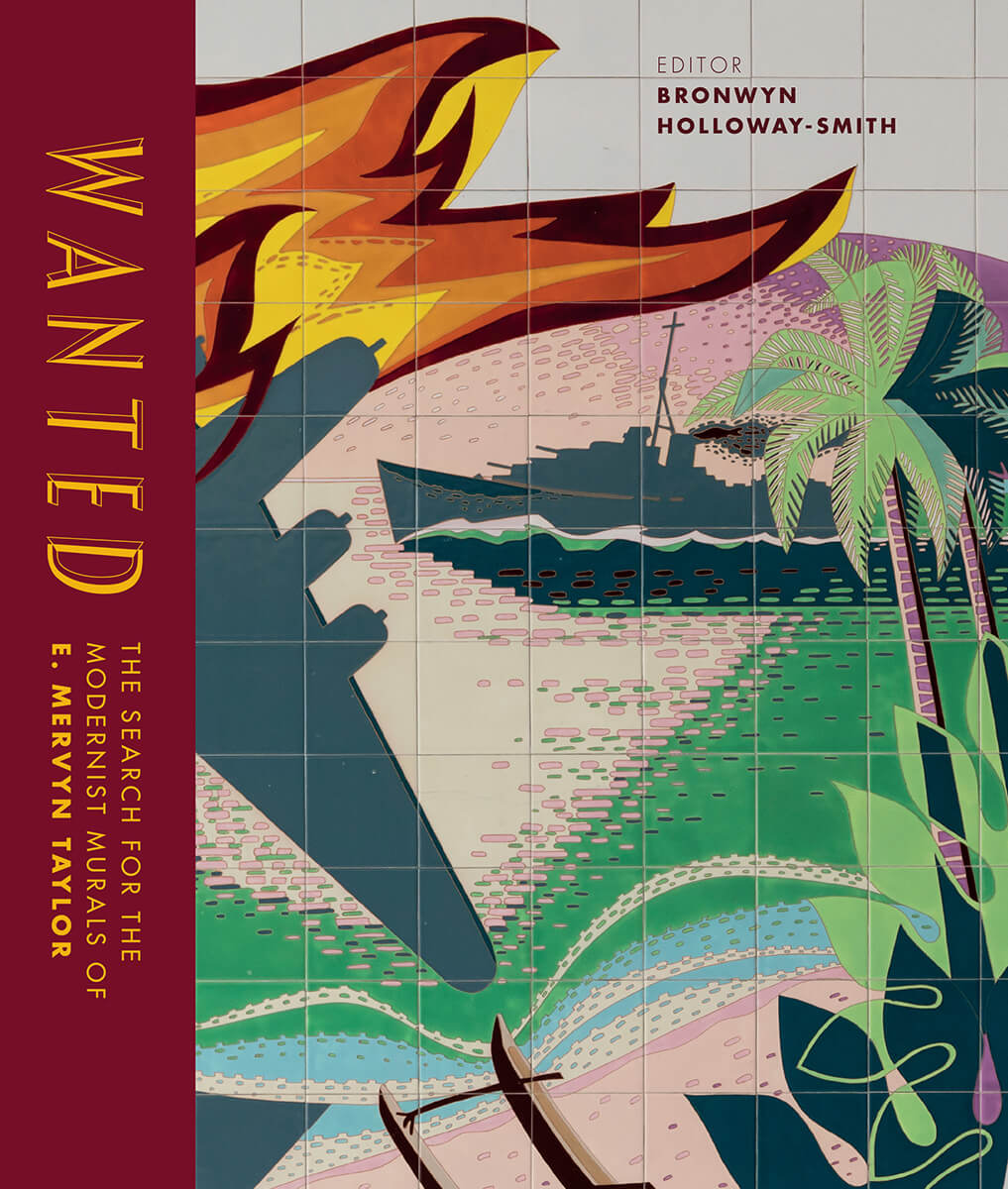

Ockham shortlisted book wins Best Cover award

Associate Professor Anna Brown and Dr Bronwyn Holloway-Smith’s book, Wanted: The search for the modernist murals of E. Mervyn Taylor, won Best Cover at the 2019 PANZ Book Design Awards.